episode 6: this feels Good!

‘Candide Overture’ by Leonard Bernstein is a fantastic piece. Fun for the listener and virtuosic for the orchestra, it bursts with energy and excitement. In this episode I share insights into the piece and I discuss the ‘feel’ of music by exploring the role of the Time Signature. Also I answer the question, ‘What is an Overture?’.

Click on the image to listen on YouTube.

listen via podcast apps

further information

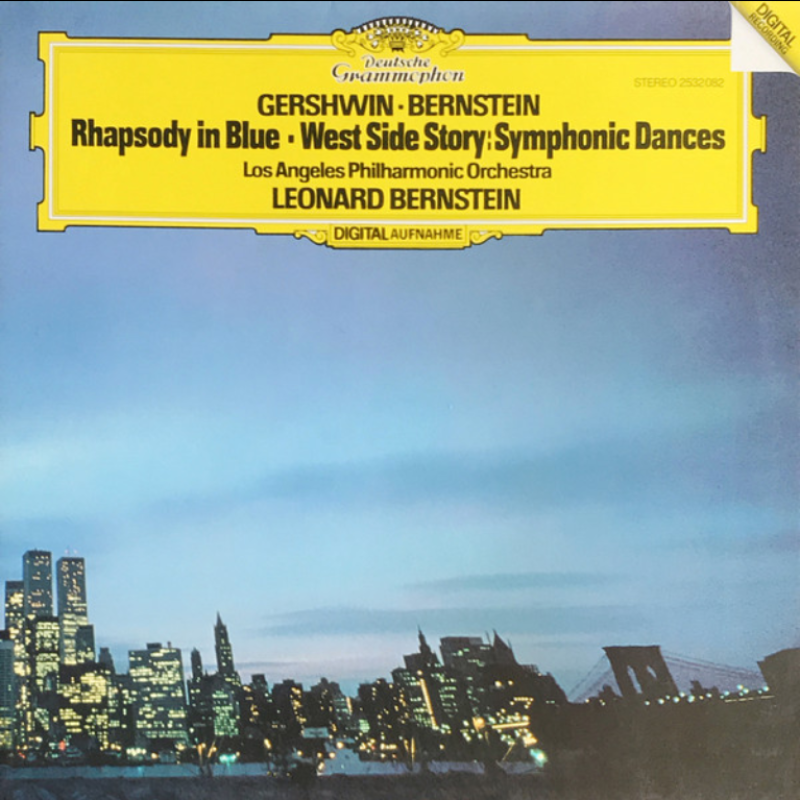

recommended recording

This episode features Bernstein’s ‘Candide Overture’ performed by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the composer.

get in touch

questions / suggestions

If you have questions or would like to make a suggestion of a piece or topic for a future episode, please get in touch via social media or email.

transcript

Hello! My name’s Scott Wilson. I’m a conductor and I’m passionate about classical music. In this podcast we discover the music of one of our greatest artforms. We listen to a new piece in each episode, I share insights into the music, and over time, I’ll take you on a journey through classical music’s composers, musicians, and history. Everything’s discussed in an easily digestible way, and no prior knowledge is needed. This podcast is for you!

Today we’re listening to ‘Candide Overture’ by the composer Leonard Bernstein. It’s a fantastic piece. Fun for the listener and virtuosic for the orchestra, it bursts with energy and excitement. I’m sure you’ll enjoy it!

[music excerpt]

This piece is an overture, and that means it’s always used as a concert opener. It grabs the listener’s attention and gets everyone pumped about what’s to come. What better way to begin than a fanfare from the brass and percussion. Following this, the woodwind scream ‘we’re off!’. They cascade downwards, and the audience is driven forwards into the piece.

[music excerpt]

How great’s that! Everything’s being thrown at you! It’s fast and joyful, like you’re on a ride at a fairground. The composer, Bernstein, has designed the ride, and the musicians have their foot on the accelerator. Everything happens so quickly that it’s easy to miss the details! But don’t worry, that’s the nature of this music!

Let’s listen again. You’ll hear a fanfare, followed by the woodwind rushing downwards. Soon after, the violins come in with a rapid melody. When you hear it, just imagine the frantic movement of the bows across the instruments and, in the left hand, the fingers racing up and down the strings to play all those different pitches!

[music excerpt]

This piece was written to open an opera based on Voltaire’s novella ‘Candide’. In his text, Voltaire points his crosshairs at the religious and political establishment. Their claim, that all human suffering is part of a divine plan, causes - according to Voltaire - people to be optimistic, even when their lives are miserable. The main character of the novella - Candide - believes, despite overwhelming misfortune, that we live in the best of all possible worlds. Voltaire’s style is ironic ridicule, and this witty, satirical plot is what inspired Bernstein to compose this opera in 1956, nearly two hundred years after the original text.

In the music we’re about to hear, the xylophone takes centre stage: the music becomes comically cartoon-like. Soon after, there’s a kind of banal and uppity music played by the brass. After something as whimsical as the xylophone melody, perhaps this uppity music represents the establishment. In this excerpt, the two qualities - the jestful and the pompous - alternate back and forth.

[music excerpt]

In this and subsequent episodes I’m taking the opportunity to explore what types of pieces orchestras play. Overture comes form the French word meaning ‘opening’. It’s how an opera begins. From a purely functional point of view, an overture’s purpose is to focus the audience. It’s a brief moment of entertainment before the story begins in earnest. And you can imagine why this is necessary. All of us miss the train we were hoping to catch, or hit traffic in the car. We arrive at the theatre with barely enough time to collect our tickets and take our seats. Having just caught our breath, and still dwelling on some problem from work, we aren’t ready to begin listening to a long story. It’s the overture that prepares us for what’s to come!

It’s not so different for the musicians in the orchestra. Playing a short piece can ease nerves and get everyone on stage feeling 100%. The music that follows an overture is likely to explore a wide range of technical challenges and emotional extremes, and this requires significant concentration sustained over a long period of time. An overture can give the musicians the opportunity to find a deep sense of focus. For the composer, it’s a chance to set the tone of the opera. Important melodies are introduced, and these often represent the characters who’ll appear in the story that follows.

Overtures like ‘Candide’ are so effective that they’ve become pieces in their own right, performed by orchestras without the opera that was designed to follow. And given that their function is to get the performance going, composers have often written overtures without any intention of writing a subsequent opera. Orchestras need pieces to start concerts, and overtures fit this purpose perfectly!

In the next episode we’ll have a listen to other music that’s been taken from operas to be performed on stage by orchestras. But for now, we return to the music. It continues to roll forwards energetically, but the sound of the orchestra has become warmer.

[music excerpt]

It’s a lovely melody. But for me, it becomes even more special at the point where there appears to be two melodies happening at the same time! The melody itself continues, but a second melody - which is what we call a counter-melody - is added. Let me demonstrate. I’ll begin by playing the melody itself:

[music excerpt]

There’s our melody: the flowing series of notes which is the most easily singable part in the music. Though we hear it on its own the first time, when it’s repeated, it’s enhanced by the addition of a counter-melody. Let’s listen to the counter-melody now:

[music excerpt]

The counter-melody is more difficult to sing, and less easy to grab onto than the melody. It’s magic is revealed only when they’re played together. Given that we can perceive the melody easily, it’s the counter-melody that brings an added richness to this moment. Here they are together:

[music excerpt]

Let’s now listen to the music as played by the orchestra, especially trying to notice the melody and also the counter-melody. If you’re listening on headphones, the melody will come slightly more out of your left speaker and the counter-melody will be more prominent in the right speaker.

[music excerpt]

It’s all over very quickly! So let’s have another listen. You’ll hear the melody in your left speaker and the counter-melody in the right speak.

[music excerpt]

Crafting the music is the composer. And in this instance we’re talking about one of the towering figures of classical music, Leonard Bernstein. His influence is hard to overstate, and even thirty years after his death, his recordings and cultural legacy continues to impact musicians, audiences, and educators. His compositions - perhaps most notably, his musical West Side Story - are performed throughout the world, his recordings as a conductor are among the most important, and his Emmy Award-winning music education programs were watched by millions. He was one of the most important classical musicians of the second half of the twentieth century.

Bernstein’s the conductor on the recording we’re listening to today. Listen to him and the orchestra letting rip in this next excerpt. The string section has the melody and, if you listen carefully, you can hear the counter-melody at the top of the orchestra’s sound, played by the piccolo.

[music excerpt]

Two episodes ago we began our journey to discover how music works. We’ve looked at melody, phrases and harmony. And this included discussions about the bass line and the chords. Today we’re going to look at what gives music its feel. This will help us uncover why it is that some music can be recognised, for instance, as a march and other music as a dance. But before we do that, we must understand pulse.

When you tap your foot along with a piece of music, you’re tapping the pulse. Sometimes people refer to this as tapping the beat, but the word beat has so many different uses and meanings that I prefer to say pulse. Pulse provides the framework on which music is built because it measures time. These measurements of time are equal and regular, and this is why we can perceive pulse so easily.

Giving the music its feel is a Time Signature. This is written by the composer at the beginning of a piece and it states how the pulses are grouped together. Typically the pulse is grouped in twos, threes, or fours. For example, the pulse in a piece of music might be grouped like this: 1 - 2, 1 - 2, 1 - 2, or maybe like this 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3, or it could be 1 - 2 - 3 - 4, 1 - 2 - 3 - 4, 1 - 2 - 3 - 4. These three different ways of grouping pulse are three different Time Signatures. So, when a drummer in a band counts in a song - something like, ‘a 1 - 2 - 3 - 4’, they’re establishing not only the pulse, but also the grouping of those pulses. And it's the grouping - the Time Signature - which gives music its feel. For a dance like a waltz, the Time Signature is in three. From the drummer, you’ll hear this: ‘1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3, boom - cha - cha, boom - cha - cha, boom - cha - cha’, and then the music will continue on in this way.

But in ‘Candide Overture’ most of the piece is march-like: the feel - the Time Signature - is usually in 2. Have a listen, and count along. ‘a 1 - 2, 1 - 2’:

[music excerpt]

Okay, so that’s a lot of information. But let’s extend it one last time. The melody we discussed earlier has an interesting pulse grouping. There’s a series of seven pulses, grouped together as two groups of two and one group of three. The pattern is as follows: 1 - 2, 1 - 2, 1 - 2 - 3; 1 - 2, 1 - 2, 1 - 2 - 3. Let’s listen to the melody, noting its different feel. Here we go: ‘a 1 - 2, 1 - 2, 1 - 2 - 3’:

[music excerpt]

Perhaps you managed to count along! If so, you were counting the grouping of pulses. And once again, that grouping is called the Time Signature, and it determines the feel of the music.

Okay, back to the music! It’s quiet, the end’s in sight, and we’re racing to get there! As you listen, keep the march feel in mind. 1 - 2, 1 - 2:

[music excerpt]

Halfway through I bet you lost your sense of pulse - I did too! In order to build excitement, the composer, Bernstein, throws the listener off course. Suddenly the music’s faster. But even more dramatic is that he, in effect, writes two Time Signatures - two different feels - at the same time. Don’t worry, we’re not going to get into this right now! But we’ll listen to it again. And to stimulate your curiosity, I can tell you that there’s a Time Signature of three happening at this speed: 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3. And at the same time, a faster grouping of three, like this: 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3, 1 - 2 - 3. And together there’s a kind of organised chaos, intended to create excitement for the listener. Enjoy!

[music excerpt]

In all this, my job as conductor is to stand there and provide a reference point for the musicians. Though the piece is dramatic - it’s loud, then quiet; fast, then faster - you might think there’d be lots of room for theatrics. But in this instance, conductors are focused on harnessing the energy of the music through very precise gestures. Small, highly-energised movements serve the musicians best: they create clarity within chaos. The musicians are playing boundlessly exciting music, and they have many notes to fit in. The conductor supports by indicating the pulse.

Well today we’ve discussed how music sits within the framework provided by the pulse, and how a grouping of pulses - which is called a Time Signature - creates the music’s feel. In the next episode I’ll be answering the question, ‘What is rhythm?’

Well here it is: the ending!

[music excerpt]

It’s no wonder this piece is a favourite of audiences, and of mine. Energy roars out of your speakers; it’s fun, light-hearted, and joyful. And there’s a sense of urgency: when listening, there’s barely enough time to hear all the information. As we listen, we hold on to what is a roller-coaster ride through the music!

Thank you for being with me for another episode of A Thousand Pictures. If you have questions or would like to make a suggestion of a piece or topic for a future episode, please get in touch via social media or email feedback@athousandpictures.com. Further information, a link to the recording featured in today’s podcast, and suggestions about what to listen to next can be found at athousandpictures.com. Or subscribe to our email list and you’ll receive this information directly to your inbox.

Today we’ve been listening to ‘Candide Overture’ composed by Leonard Bernstein. I recommend the recording by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the composer.

And finally, please subscribe, please rate and review, and please share this podcast with others. Your support is valuable and it’s appreciated: together we can create a community which celebrates classical music! Now go and listen to this wonderful piece, and get out there and hear a performance by your local orchestra!

[music excerpt]