episode 17: SUPERHUMAN VIRTUOSITY

‘Piano Concerto no. 2’ by Sergei Rachmaninoff is a vehicle for virtuosic performance. It requires the pianist to display superhuman levels of physical prowess! In this episode I share insights into the piece, I discuss pianos, and we explore virtuosity in classical music.

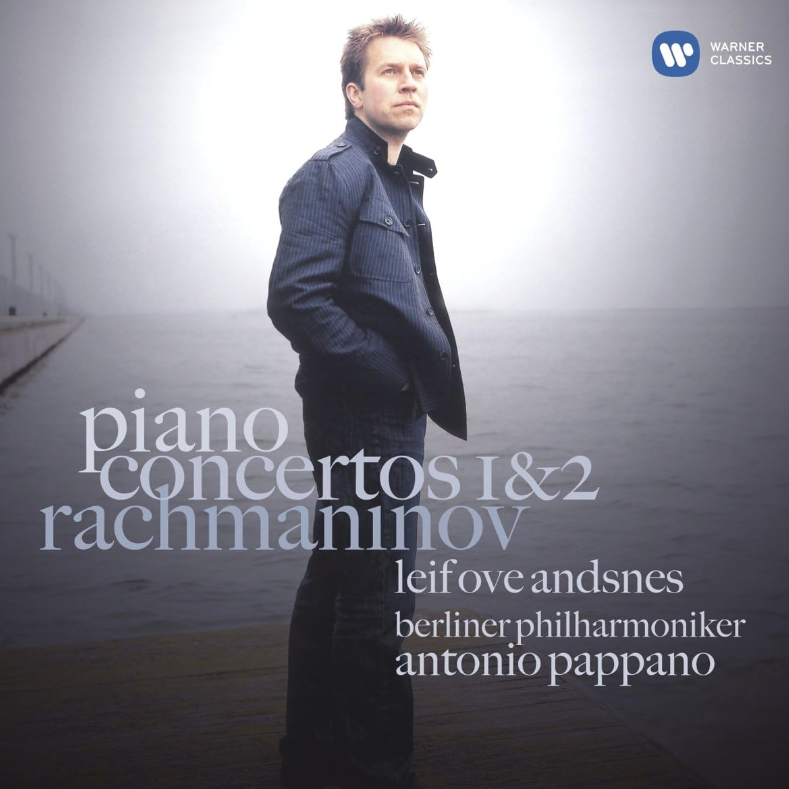

Click on the image to listen on YouTube.

listen via podcast apps

further information

recommended recording

This episode features ‘Piano Concerto no. 2’ by Sergei Rachmaninoff performed by Leif Ove Andsnes with the Berliner Philharmoniker conducted by Antonio Pappano.

get in touch

questions / suggestions

If you have questions or would like to make a suggestion of a piece or topic for a future episode, please get in touch via social media or email.

transcript

Hi! My name’s Scott Wilson. I’m a conductor and I’m passionate about classical music. In this podcast we discover the music of one of our greatest artforms. We listen to a new piece in each episode, I share insights into the music, and over time, I’ll take you on a journey through classical music’s composers, musicians, and history. Everything’s discussed in an easily digestible way, and no prior knowledge is needed. This podcast is for you!

Today we’re listening to ‘Piano Concerto no. 2’ by the composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. This is one of his most popular pieces. And it’s hard not to like it. Of course the music is great. But also, the piece is a vehicle for virtuosic performance. For the pianist, it’s a superhuman display of physical prowess! I hope you enjoy it!

[music excerpt]

This is the first melody in the piece. But it takes some time to arrive at this music. The piece itself begins from silence. There’s a large orchestra on stage, but all eyes are on the pianist. The pianist lifts their arms and plays a chord, followed by a low note. Another chord, and then that same low note again. It sounds like the tolling of a bell. With each new chord, the sound of the piano increases. The first chord was quiet; it’s heard from inside the piano. But then the sound grows until it reverberates through the concert hall. The piano lays down the gauntlet to the orchestra and calls it in with these four chords:

[music excerpt]

At the command of the pianist, the orchestra joins and the melody begins.

So, let’s now hear it! Imagine yourself in a silent concert hall. There’s an orchestra on stage, and at the front, the lone pianist sits at the piano.

[music excerpt]

We’ve arrived at the melody we heard at the beginning of the episode.

This piece was first performed in 1901, and it was important to the composer, Rachmaninoff. His ‘Piano Concerto no. 2’ was his re-emergence following four difficult years with depression. Given the context within which the piece was written, when I hear this music I imagine Rachmaninoff himself at the piano. At the opening of the piece, it’s as if his confidence grows alongside the increasing volume of the piano. And when the orchestra enters, it’s because the pianist - the composer himself - has willed it to play. Rachmaninoff plays the piano, and he hears the orchestra’s sound surrounding him.

Let’s listen to it. Perhaps you envisage a similar scene when you hear this music?

[music excerpt]

We hear an endless flurry of notes from the pianist. To continue my imagined narrative, perhaps those notes represent Rachmaninoff’s steadfast determination; at the piano, he’s powerfully driving the music forwards.

In contrast, the melody is actually very straightforward. It begins like this:

[music excerpt]

When you hear the melody on its own, it's surprising to realise how few notes there are. It turns out that it’s the relentless notes from the piano which create the momentum in the music. The piano is the engine. For every note played by the orchestra, the pianist plays many, many more. For example, in the time that it took me to play the ten notes of the melody just now, the pianist would’ve played around eighty notes!

Let’s listen a little further on. Can you hear the urgent energy created by the piano, and at the same time, an expansive melody played by the orchestra?

[music excerpt]

Over several episodes I’ve been exploring the question, ‘What makes a performance thrilling?’. We’ve looked at the historical circumstances of the performer and the conviction and virtuosity of orchestras and composers. In the next episode we’ll discover the conviction of individual musicians within an orchestra; but today’s episode provides an opportunity to see how the virtuosity of a soloist can contribute to a thrilling performance.

In Episode 9 I said that a concerto is a type of piece that features a soloist with an orchestra. These pieces - concertos - allow a composer to exploit the full range of physical and musical capacity of musicians. From one perspective, it’s the closest music gets to sport. Virtuosic soloists are in peak physical condition and are able to push themselves to the limits of what the human body can achieve.

Though it’s the composer that makes the demands upon a soloist; in part, virtuosity has been driven by audiences. Audiences seek out new, original-sounding music, and crave ever-more impressive feats of instrumental athleticism. So the technical difficulty faced by soloists has had a tendency to increase over time. The challenge for the soloist is the sheer coordination of multiple physical actions occurring simultaneously, and in quick succession. And there’s a requirement for fine accuracy too. For instance, a pianist might need to make a very large shoulder movement to take one arm from the middle to the outer side of the instrument. But, following that large movement, their elbow, wrist, and multiple finger joints need to work in sympathy, perhaps in order to execute a delicate movement. All of this might need to take place within an incredibly short space of time. And every physical movement impacts the sound that’s created. So, the requirement isn’t just to achieve the physical movements that allow all the pitches and rhythms to be played. Instead, the musician must achieve those movements whilst also caressing their instrument in a way that ensures that beautiful sound is always created.

All of this is learned and refined over many years of dedicated practise. In fact, that statement doesn’t quite do it justice. Virtuosity at the level that’s being demonstrated in the piece we’re listening to today, requires an almost single-minded focus. This begins at a young age and then must be sustained for many years. Much must be sacrificed in order to achieve true virtuosity. Alongside this there’s the necessity of studying with a master. This musician passes on knowledge of the craft which was obtained by the very same process that their student is experiencing. And all of this takes place within centres for excellence like music schools, conservatoires, and universities.

And even then, it isn’t enough. Virtuosic soloists must have the audacity of vulnerability. Vulnerability sets the very best musicians apart. It’s theoretically possible for many to achieve the physical brilliance of technical accomplishment. But the performers who deeply move an audience are the ones who allow us to see into their soul. They pour everything into their performance: they’re communicating through the music. It’s a little dramatic, but I’ve often said that part of a musician dies each time they perform. Something from deep inside that musician is given away - or, revealed - to their audience, and they can’t get it back. So, whilst it’s the technique that provides the ability to be in ultimate physical command of the instrument; the technique is merely a means to achieving the openness, vulnerability, spontaneity, and freedom that allows a great musician to communicate with an audience.

Listen to the wonderful playing in the next excerpt. It’s slower than what we’ve heard previously, and therefore, theoretically it’s easier to perform. But you’ll hear true virtuosity. Everything the pianist does is made special for the listener. We feel as though the pianist is communicating directly with us. In the hands of this virtuoso musician the pitches and rhythms become music.

[music excerpt]

We’re going to listen again. Yes, there’s a gorgeous melody. But even more special is listening to how the running low-pitched notes provide the context for that melody. They shape the music’s emotion. Sometimes these notes flow downwards, but at the perfect moment they turn back, ascending towards the melody. And then there’s moments of subtle beauty when the bass line and the melody coalesce. These moments are compositionally special. The music becomes poignant, perhaps even uplifting.

[music excerpt]

Most of that music was piano alone. But, a beautiful moment occurs when the violas enter for just a few notes. All they play is this:

[music excerpt]

When we listen now, hear how the two parts interact: the piano and the violas are communicating with each other. It’s a moment of conversation.

[music excerpt]

And then the piano’s off again, striding forwards on its own.

A little further along in the piece, the conversation between soloist and orchestra continues. This time the cellos make a similar statement to what we just heard, but they pursue their idea further. The conversation is, for a moment, being driven more by the orchestra than the soloist. For a listener, the emotional impact is different. We’re hearing the orchestra - represented by the cellos - pursue its side of the story. Following this, listen to how the piano responds - answering the cellos, as if chatting between friends.

[music excerpt]

For me, concertos are amongst the most special experiences for a conductor. Rather than taking prime responsibility for the music, you must work with the ideas, experience, and requirements of the soloist. This seems like it could be an opportunity for an abdication of the conductor’s duties. Or, if not that, it could be assumed that there’d be a tendency to water down each musician’s perspective through compromise. But, it isn’t that at all. What makes conducting a concerto so special isn’t compromise, but empathy. Two musicians bring to the table the weight of their knowledge and abilities. Magic can be created in the grey area that exists between the two inevitably different views on a piece. The responsibility to remain utterly driven by personal conviction, whilst remaining open to unexpected possibilities, opens the door to the potential of achieving the very greatest music-making.

Listen to this next excerpt. The music floats. Partly this is the composition, but also it’s an example of empathy in performance: the conductor and soloist are feeling the music ‘as one’.

[music excerpt]

Over the past two episodes I’ve discussed two orchestral instruments: violin and timpani. But today I’ll talk about the piano. What’s interesting is that the piano isn’t really an instrument of the orchestra. Although it’s used frequently as a solo instrument, it’s only very occasionally used within the orchestra. This might be surprising, as the piano is one of the most widely played instruments, and certainly it’s the most popular classical instrument. But, its sound isn’t usually considered well suited to the orchestra. In particular, it doesn’t blend very well with the other instruments.

But it remains an important instrument in classical music, not least because it’s one of the few instruments that genuinely allows a player to play both melody and accompaniment at the same time. Meaning, in the left hand a bass line and chords can be played, whilst the right hand plays a line that could be sung. This explains the piano’s wide use in a variety of genres, from classical music, to jazz and pop, and even why it’s the instrument of choice sitting in the corner of pubs and clubs patiently waiting for someone to lift the lid and tickle the ivories. And in fact, that phrase relates to its construction. Historically the white keys of the piano were capped in ivory, whilst the black keys were made of ebony. The configuration is white keys, interspersed with black keys. The pattern of three black keys, then a gap, and then two black keys, causes each key on the piano to have a visually unique position compared to all others. It's this configuration that allows a pianist to know which pitch they’re playing.

When any one of the 88 keys of a piano is depressed - and of course, multiple keys can be pressed at the same time - a felt hammer inside the piano launches itself at the strings. When it connects, it immediately rebounds leaving the strings to vibrate. The strings produce pitch because they’re under enormous tension. And the sound of the vibrating strings is amplified by the components within the instrument.

If the player leaves their finger on a key, the strings continue to ring. The moment their finger leaves the key, the strings are dampened. However, the pianist has the option of using a foot pedal to allow the strings to continue to vibrate even if their fingers have released the key. The use of this pedal is synonymous with piano playing, and it’s what allows the piano to have that full, resonant sound of many notes being played at once. Also, there are two other foot pedals. One of them alters the way in which the hammers come into contact with the strings: it creates a sound that’s quieter and less full in tone. And the third pedal interacts in a more complex way with the dampers, but ultimately it allows the pianist to sustain some pitches indefinitely, whilst others are immediately dampened after they’re played.

The basic principles of the instrument remain the same whether the piano is an upright or a grand. But, it’s a grand piano that’s preferable in all circumstances in classical music because of the greater quality and variety of its sounds. And this was a sound that came into existence around the year 1700. At the time, the most widely used keyboard instrument was the harpsichord. This instrument has a similar arrangement of keys, but those keys pluck the strings. This plucking led to an instrument that could effectively only produce one volume. The piano superseded the harpsichord in part, because the player had much greater control over the volume they could produce. In fact, the original name in Italian was ‘un cimbalo di cipresso di piano e forte’. This translates to ‘a keyboard made of cypress wood with quiet and loud’. Later this was shortened to the ‘pianoforte’ - the quiet-loud. And the instrument is now known simply as the ‘piano’.

Increasing the breadth of volume and colour of sound that a piano could achieve was an ongoing process of refinement. Eventually the instrument developed the capacities that allow it to be ideal for the kind of music envisaged by Rachmaninoff. In this next excerpt listen to how the composer exploits the huge volume possibilities of the modern piano. It performs on an equal basis with the entire orchestra.

[music excerpt]

As the music builds towards the climax, I again like to imagine the composer, Rachmaninoff, playing the piano. As it turns out, he was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th Century. He had large, long-fingered hands and was able to play with immense power. And his compositions were built around his strengths. His scores often demand a way of playing that requires the fingers to be spread incredibly widely, and also the pianist must physically throw themself behind the chords they play in order to produce enough sound to compete with the orchestra.

Listen to the power of this piano playing.

[music excerpt]

The narrative here is compelling. The orchestra and pianist have battled through the music we’ve just heard. It’s like neither were prepared to lose ground against the other. And after this struggle - which produced the climax of intensity in this piece - we now return to the opening melody. For me it’s a devastating moment. Despite the efforts so far, we haven’t arrived at a point of consensus. The pianist and orchestra remain in opposition, relentlessly pushing on with defiant strength.

[music excerpt]

This is such fantastic music. Utterly gripping in its emotional narrative and compelling in its virtuosity. Hearing and seeing this piece performed live can be unforgettable. In reality there are very few people who achieve the mastery required to be able to perform this piano concerto. It’s reserved for those individuals who somehow go beyond normal levels of human achievement. In short, the pianist’s technical, physical ability - as well as their willingness to perform with complete abandon, with genuine vulnerability - is incredible. These virtuosic musicians are able to inspire.

Thank you for being with me for another episode of A Thousand Pictures. If you have questions or would like to make a suggestion of a piece or topic for a future episode, please get in touch via social media or email feedback@athousandpictures.com. Further information, a link to the recording featured in today’s podcast, and suggestions about what to listen to next can be found at athousandpictures.com. Or subscribe to our email list and you’ll receive this information directly to your inbox.

Today we’ve been listening to the first movement from ‘Piano Concerto no. 2’ composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff. I recommend the recording featuring the pianist Leif Ove Andsnes, with the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Antonio Pappano.

And finally, please subscribe, please rate and review, and please share this podcast with others. Your support is valuable and it’s appreciated: together we can create a community which celebrates classical music! Now go and listen to this wonderful piece, and get out there and hear a performance by your local orchestra!

[music excerpt]